Aryan Afrouzi’s credit cards were maxed. He describes the weeks leading up to the news as the worst of his life, but Alexander Stratmoen didn’t know the full extent of his friend’s financial turmoil as the car crawled through the McDonald’s drive-thru. It was 11:35 p.m.and deep into a frigid Canadian November when the call came.

The chicken nuggets were easier for Afrouzito digest than being told over the phone that Voltra, the company he co-owns with Stratmoen, had attracted a $1.8-million investment led by Contrary, with participation from Hanover and Velocity Fund. Afrouzi called his parents from Voltra’s headquarters at Velocity’s downtown Kitchener hub and they were ecstatic, but he couldn’t immediately share their level of joy. He struggled to comprehend the enormity of what happened during a fast-food order.

“I was literally a few days away from insolvency," Afrouzi recalls, noting that would’ve likely spelled the end of the Voltra project that he risked everything for.

Instead, Voltra now has the capital and clout to begin to revolutionize North America’s electrical grids.

Improving the EV experience

It all starts with electrical vehicle (EV)chargers. For the growing cohort of EV owners Stratmoen says the gamble of rolling into a parking lot without knowing whether the charger will work or not is “destroying the driving experience.”

Individuals with EVs often negotiate a wide range of apps on their phone for the various types of software found at charging stations, and even those apps can frustratingly lead drivers to out-of-service chargers as their vehicle is running out of power. A Havard Business School study of 1 million EV charging station consumer reviews published in June 2024 found that 22 per cent of non-residential chargers in the United States weren’t functional. Statistics for Canada’s EV landscape are limited.

Companies with fleets of EVs regularly lean on three or four software subscriptions – such as one for managing chargers and another to track battery usage – and awkwardly integrate them into their own software, creating what Stratmoen describes as a “huge, brittle mess.”

Voltra’s solution is to create modular components so businesses, and other places that require EV chargers like condos, can build their own one-stop service. The company introduced Charge, a real-time dashboard for managing everything related to EV usage, on May 14, 2025. Charge is affordable and accessible to developers who aren’t experts in the field of EV charging.

“We’re trying to make this software so much more convenient. We really want to avoid this world where you need third-party products to make your car work,” Stratmoen explains.

“We think those features belong in the places where you're expecting them – you should go into a Maps app and be able to connect your car there.”

North America is “ill-prepared”

Studying EV chargers offered Voltra an objective view of electrical grids, and it was concerning.

The centralized grid system is already flagging due to unprecedented electrical demand. EVs could draw nearly five per cent of theUnited States’ electricity output by 2030, according to ContraryResearch. That pressure on the grid coincides with other modern challenges, including data centres powering AI and cloud computing, growing populations, increased use of air conditioning and heating in extreme weather events, and the tougher job of managing supply and demand while energy can be drawn from more renewable sources, like solar and wind.

“It’s scary how ill-prepared we are in North America,” Afrouzi says, comparing today’s electrical grid to a leaning Jenga tower.

More than 31 transmission lines connect theUnited States and Canada. Although there are discussions over how Canada can be less reliant on the U.S. since President Donald Trump took a hard stance on tariffs, both countries will continue to share many of the same problems in their interconnected, aging electrical system.

Contrary Research found around 70 per cent of transmission lines in the United States are more than 25 years old, meaning many are approaching or have surpassed their expected lifespan. In the next 10 years, Canada is expected to be exposed to energy shortages in eight of its 10 provinces, withNova Scotia and Quebec worst affected, according to April’s report from the NorthAmerican Electric Reliability Corporation. Canada dealt with significant power failures in Alberta and Prince Edward Island in the first two months of 2025 alone.

The strain on the electricity grid must be addressed in smarter ways.

That’s where EVs come back in. Through conversations with industry experts, Afrouzi and Stratmoen found that operators at the grid’s core are struggling to detect where EV chargers are, so can’t begin to avoid the spikes unsettling the electricity web.

Voltra’s solution is to decentralize the grid. The company has gathered data on EVs that, with APIs, can inform power plants on how to better manage the electrical load and avoid blackouts with a flood of real-time information. It would no longer be a guessing game of where EV chargers are and how much power they need when the grid’s edge and its interior can communicate. The potential of this interconnected software reaches far beyond EV chargers: eventually, many more physical assets around the grid’s outskirts can become integrated and effectively produce a clear electricity roadmap across the continent. Voltra can form the operating system of the future with wires and wireless signals.

“All of that information directly informs grid operations and leads to more stability and security of North America's power grids,"Stratmoen says.

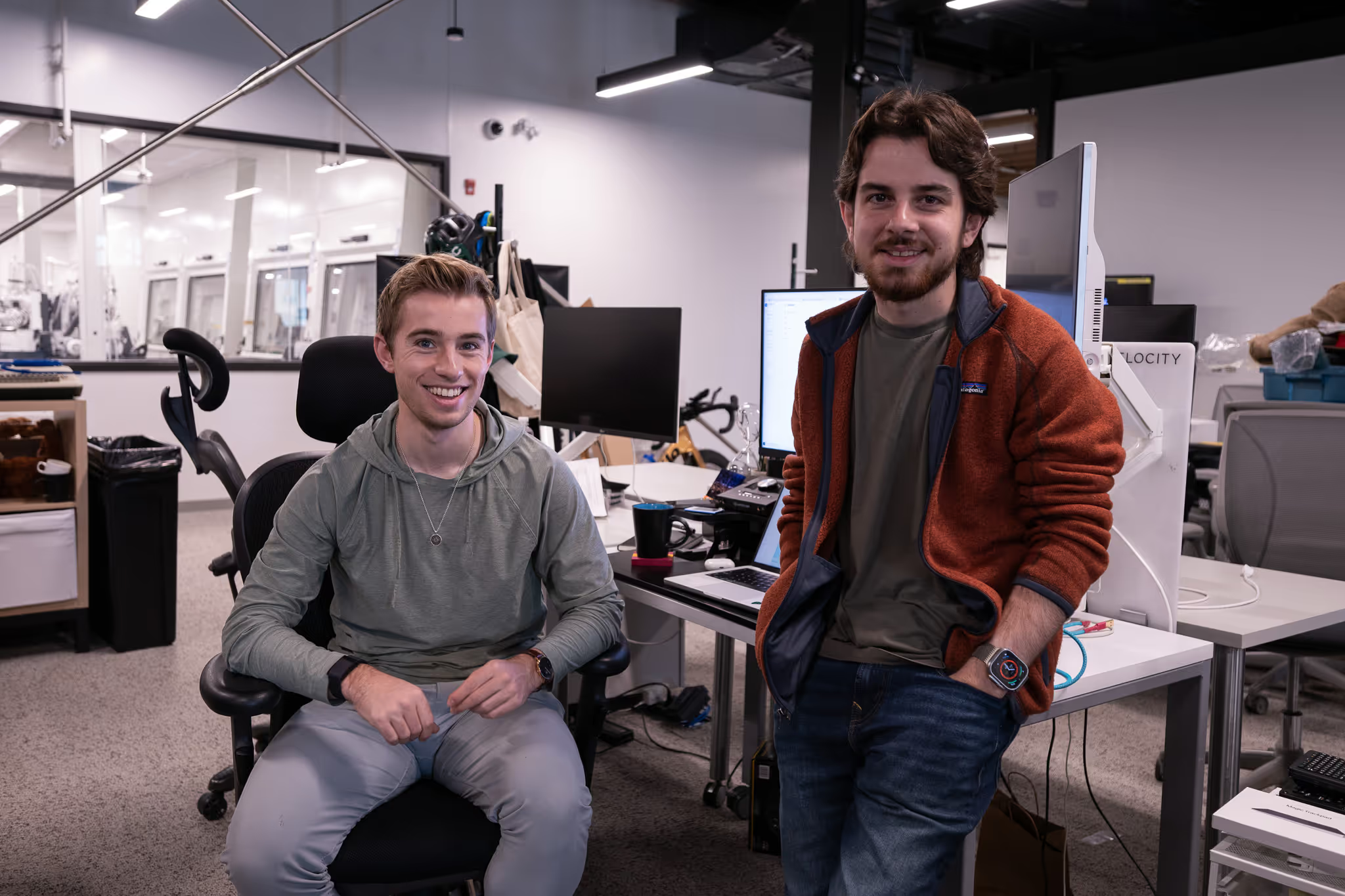

Waterloo’s global outreach

Afrouzi and Stratmoen, both 22 and born just days apart, are happy to start their revolution from Canada. A trip to Silicon Valley last fall attracted the investment that kept Voltra on its mission to ease frustration at EV charging stations and safeguard electrical grids. It also gave them a greater appreciation of the University of Waterloo’s place in the world tech landscape.

"Waterloo is way more famous in San Francisco than it is here, for sure,” Afrouzi says, reflecting on how tech leaders initiated conversations with him on the street because he was wearing aUniversity of Waterloo sweater. “The freaking founder of Node.js, a huge JavaScript framework, was like, 'Hey, you went to Waterloo. Let's talk.'"

"No one questions your ability to build,” Stratmoen adds. “If you went to Waterloo, it's like, 'Oh yeah, you'll be able to build this. That's fine.’”

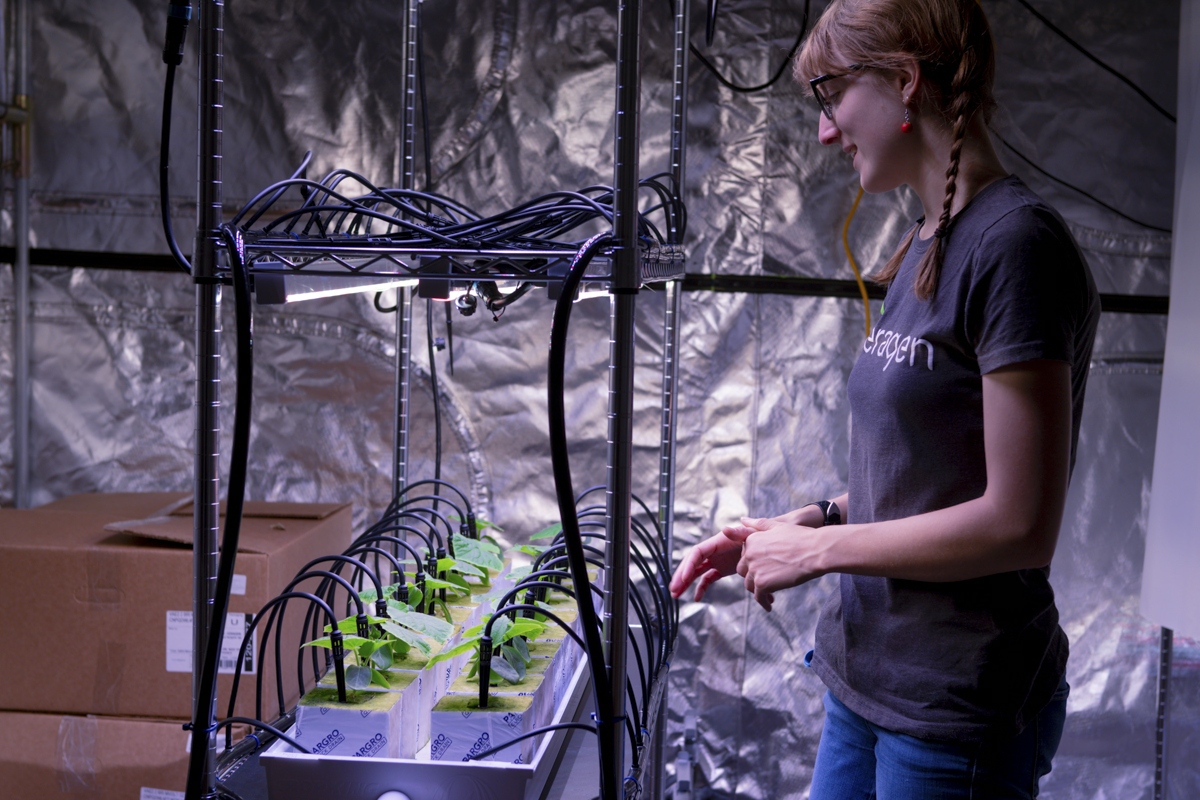

But being in the world’s tech capital isn’t quite like home. TheBay Area has the latest tech innovations, a riot of parties, and is a hive of inspiration and networking opportunities, but those attractions can also be a distraction from the task at hand. Waterloo is where Afrouzi and Stratmoen feel they can focus, working deep into the night before crashing at Velocity in the 2046 meeting room in their sleeping bags.

“It’s the only place in the building where we know how to turn the lights off,” Afrouzi admits.